What’s the difference between fraud vs. scams?

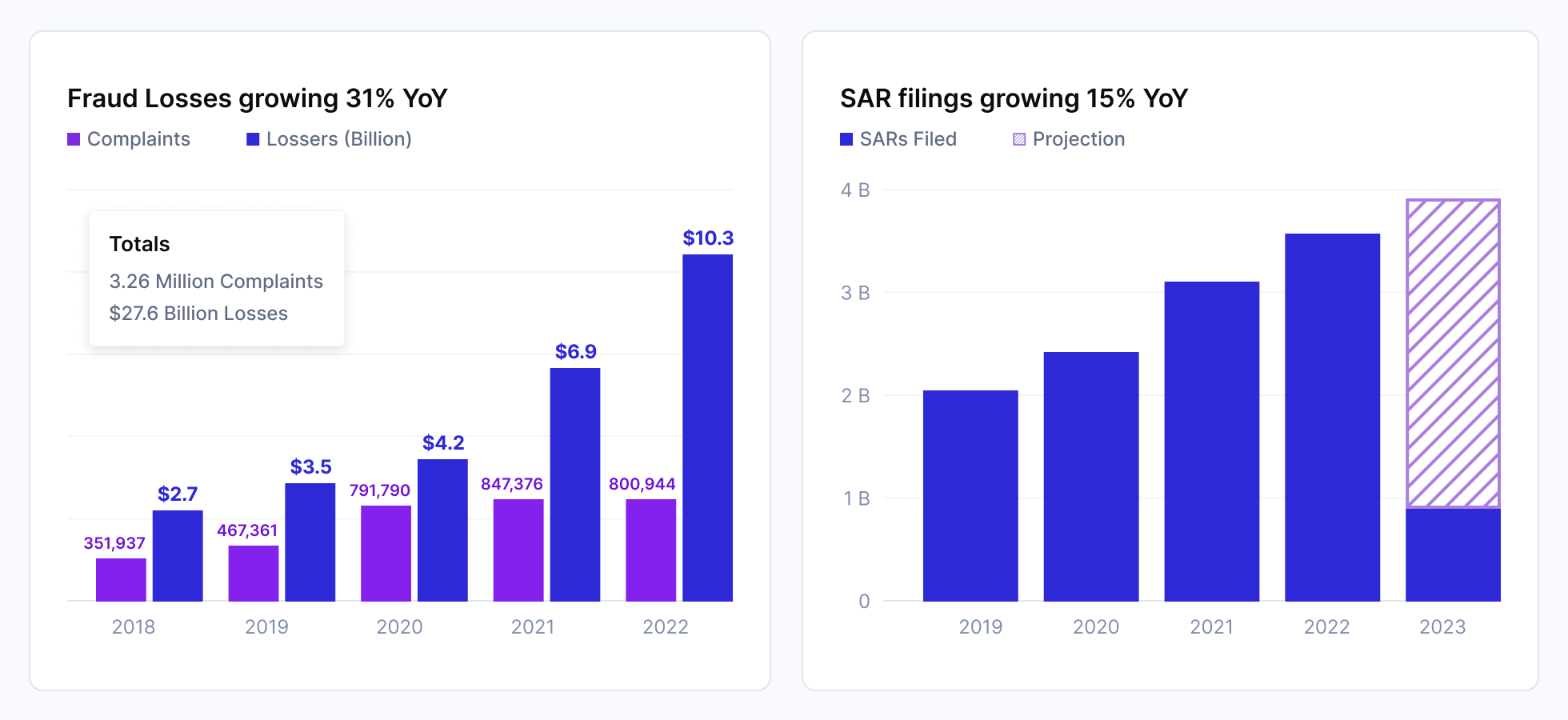

In 2022, the FBI reports that scams and identity theft losses skyrocketed to $10.3 billion, up from $6.9 billion the previous year. Globally, scams drove over $1 trillion in financial losses in 2023. In the UK, it’s now the #1 fraud issue and discussed daily on the BBC morning shows.

Yet, despite these staggering figures, awareness and understanding of these crimes remain surprisingly low.

When is it a scam, and when is it fraud? And who's liable?

Well, it depends.

Let's start with some examples and definitions

Fraud vs Scams Defined

Fraud is an umbrella term for any deliberate deception used for financial or personal gain, and encompasses many different types of attacks. Scams are a type of fraud where a criminal uses schemes or tricks to con someone out of money for personal gain.

- Fraud example: Using a stolen credit card to buy high-priced goods

- Scam example: Using a phishing email to convince someone they owe taxes or are due a refund as a front to collect personal or financial information

If a consumer's account is taken over and the fraudster makes payments, this is fraud.

However, if the consumer is tricked into sending money under false pretenses, this is a scam.

Fraud is when the bad actor moves money illegally

A scam is when a bad actor uses communications like telephone or email to trick someone into moving money.

Fraud vs Scams and the Law

Fraud is illegal in the US under a patchwork of laws:

- Fair Credit Billing Act (FCBA): Protects consumers from unfair billing practices and provides a mechanism for addressing billing errors in credit card accounts.

- Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA): Protects users of electronic fund transfer systems, including provisions for lost or stolen cards.

- Truth in Lending Act (TILA): Limits liability for unauthorized credit card charges and outlines disclosures that lenders must provide.

- Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act: Criminalizes identity theft and allows for restitution to victims.

- Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA): Promotes accuracy and ensures the privacy of information in credit reports.

The following two laws cover scams:

- Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA): Addresses scams via phone calls and messages, including telemarketing fraud.

- CAN-SPAM Act: Regulates commercial email and sets requirements for commercial messages to combat email scams.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Department of Justice (DoJ), and Federal Reserve collectively regulate the Telco and financial institutions to ensure these laws are enforced and scams and fraud are stopped. The UK has similar laws: The Fraud Act, Consumer Credit Act, and Data Protection Act.

Immediately, it’s clear that fraud law focuses on financial transactions, and scam law focus on communications (except, notably, social media).

The gap is between the two.

Scams can easily become fraud.

If someone does lose out to fraud or is scammed, there are varying liability frameworks to cover how consumers get refunded. The most well-known is with credit and debit cards.

Fraud vs. Scams with Cards

Fraud or scams are both investigated by banks and merchants if a consumer reports a dispute. The dispute is central to any type of fraud or scam attack in cards.

The process is as follows:

- Card holders can issue a “dispute” of any transaction, usually by contacting their bank

- The bank will investigate and pass the dispute to the merchant

- The merchant will investigate and can either issue a refund or (chargeback), or challenge the dispute by sharing compelling evidence.

Visa and Mastercard publish a comprehensive set of rules (scheme rules) about handling a consumer dispute and the refund process (chargebacks). This includes everything from reason codes (why the consumer is making a dispute) to evidence submission by the issuer, merchant, and arbitration.

Card fraud examples: using stolen or lost cards to make a purchase, using someone’s compromised card details to make an online purchase (card-not-present fraud).

Card scam examples: Sending phishing emails or websites to trick someone into sharing their card details.

Fraud vs Scams with Wires, ACH, and Push Payments.

ACH, Pix, UPI, Faster Payments, and Wires are “push” payments. They’re initiated by the consumer or business wishing to pay. We can split these into two categories.

Unauthorized payments

Authorized payments

In the United States, unauthorized payments on these networks are covered by Regulation E of the Electronic Funds Transfer Act (EFTA). It establishes basic rights and liabilities and is managed by the CFPB.

Each network has its own rules and liability frameworks. But broadly, if a consumer reports an unauthorized payment, a bank will investigate and must, by law, compensate them if evidence of fraud is found (for example, if the account is compromised and the fraudster can log in and drain the account). This pattern repeats itself globally, albeit with other laws.

Scams, however, are a different issue. If a consumer is tricked into making a payment but authorizes the payment to the bank or financial institution, the transaction looks legitimate. Authorized payments are not covered by Reg E or its equivalents internationally, nor are there well-developed frameworks for consumer refunds (although this is changing).

Bank fraud examples: unauthorized wire to a different account, linking a stolen account to a fintech app to make a payment, purchasing mule account services to launder money.

Bank scam examples: social engineering attacks such as the grandparent scam, where scammers impersonate a family member in distress needing immediate financial help, or the “Nigerian Prince” scam, where victims are promised a large sum of money in exchange for transferring funds out of the country.

Fraud vs Scams with Real-Time Payments (RTP)

Real-time payment networks like Pix, UPI, FedNow, and Faster Payments are push payment methods that settle instantly. A consumer who sends a FedNow or Faster Payment will see their balance reduced immediately. This is a fantastic user experience and is gaining significant popularity.

The US has wallets like CashApp, Venmo, and Zelle enabling this functionality, and in July of 2023, launched FedNow and now has more than 400 financial institutions live.

Internationally UPI has over 300m users; Faster Payments has been live with every UK bank account since 2008. In Brazil, PIX has been used by 140 million people, 80% of the adult population, and has grown 70% YoY.

Like with ACH, Wires, and other non-instant payment types, if a user’s account is taken over and an unauthorized payment is completed, they’re covered by existing fraud liability frameworks such as Regulation E.

Real-time payments with instant settlement make scams much more effective.

With Wires and ACH, the delay to settlement would allow financial institutions to investigate and potentially return funds to a payment sender if evidence of a scam is found.

- Real-time payments are often final and cannot be reversed

- By the time the scam is discovered, the funds may have already moved on to a 3rd, 4th or even 5th account or wallet

The issue with faster payments is not just the first transaction but the subsequent transactions and the ability to make following the trail of transactions increasingly difficult for any single financial institution, wallet, or service.

* Note that Zelle does have a clawback mechanism for financial transactions on its network

RTP fraud examples: Insider fraud or your average ATO, typically achieved through phishing, malware, or purchasing a compromised account.

RTP scam examples: Impersonation scam where a fraudster poses as a trusted entity like a government official and convinces the victim to make an RTP to a fraudulent account.

Authorized Push Payment (APP) Fraud

Authorized Push Payment (APP) fraud occurs when individuals are deceived into paying a fraudster by a scam. The victim authorizes the payment, unaware they are being tricked into sending funds to a fraudulent recipient. In some cases, because the payment had been authorized, financial institutions would not refund consumers or businesses who were victims of scams.

APP fraud is where scams and fraud meet and happen instantly.

It currently accounts for 40% of all fraud in the United Kingdom and is the fastest-growing fraud type in the US, UK, and India. It is expected to double in the next 3 years.

Given its extremely rapid growth, there are several common approaches to managing this emerging risk.

APP Fraud examples: Similar to the above, ATO and business email compromise.

APP Scam examples: Romance scams and investment scams.

Approaches to Manage Scams

- Education via consumer and business scam warnings. Aim to help the potential victim slow down and prevent a scam from occurring. Many merchants such as Amazon and Walmart, regularly send these warnings to customers. Most digital banking apps and payment platforms have this service live today (e.g., the below).

- Data confirmation and sharing. The UK has implemented a confirmation of payee service that attempts to match the payment recipients' names to their account details. Venmo and CashApp may ask users to input the phone number of the recipient if they believe the transaction is high risk. If these details do not match, some banking applications will not allow the payment to complete or issue further warnings to the sender.

- Regulation refunds and liability sharing. The Payment Services Regulator (PSR) in the United Kingdom has published a model that proposes sharing liability between sending and receiving financial institutions or payment companies 50/50 if APP fraud is discovered.

- Clawback (chargeback) mechanisms. Zelle has implemented a scheme rule to allow financial institutions to attempt to claw back any funds if APP fraud is discovered.

- Scam detection in digital wallets and payment solutions. If a user has just signed up for a new service, several factors may indicate a higher risk of a scam in progress such as the presence of remote screen-sharing software, or taking screenshots. Signals taken from the device before a payment happens can help wallets and payment providers slow down or prevent entirely authorized push payment fraud (for example, by insisting a user call their bank to complete a payment)

Scam and Fraud Detection: The need for a holistic solution

The ability to detect scams relies on data points from social networks, email, telcos, bank accounts, merchants, wallets, and devices. It is now common practice in fraud detection to use many of these sources to identify risky behavior by users, but the data is often fragmented or inaccessible entirely.

At Sardine we’re working with merchants, financial institutions, Fintech companies, Crypto wallets, technology providers, email data providers, and telcos to bring together the most complete picture possible.

However, scam detection is only as effective as our ability to work together across industry lines.

If you’re interested in learning more about Sonar, our industry intelligence and data sharing platform, please contact us or visit the Sonar website to learn more.